The best thing in those online surveys is they can be completed in less time, even more, flexible as they will be in an easier format than compared to conventional paper surveys. Then every company started utilizing those surveys and have been following their outcomes. Taco bell a famous fast food restaurant chain that is an American origin is not an exception in this.

The publication’s annual fast food survey, released Wednesday, found giants like McDonald’s, KFC, Burger King, and Taco Bell all lagging behind their newer, hipper fast-casual counterparts, like In-N-Out Burger and Chipotle.

“After devouring 96,208 meals at 65 chains, Consumer Reports readers told us that quality of the food has become more important in their dining decisions, and convenience of location is less so,” the Consumer Reports release on the study read. “They could be reasons the traditional fast-food chains are losing their edge: Diners, especially younger adults in the millennial generation, maybe more willing to go out of their way to get a tasty meal.”

Taco Bell is an American chain of fast-food restaurants and is a California origin, also a subsidiary of Yum! Brands, Inc. These restaurants serve a variety of Tex-Mex(Texas-Mexican) foods that include tacos, burritos, quesadillas, nachos, novelty, and specialty items. Glenn Bell is the founder of Taco Bell Restaurant who is behind the success of the company.

They have started more than 7000+ stores all around the world from its origin in 1962. That figures can simply show how a successful brand TacoBell is and how it is growing day by day. And for such a large firm there is a tremendous requirement to know the feedback of their customers. Then in such a niche space, they started availing the services of tellthebell.com where people can give feedback on their visit to the TacoBell store.

The survey is conducted to know what the customers think about the food and services provided by Taco Bell, what their needs are. So, be honest and give your genuine feedback and accurate information as much as possible during the survey. It will be extremely helpful to assess the company’s performance and give the best experience for the diners.

Eligibility to enter the survey and the drawing

To join the survey, participants need to fulfill some requirements. You can also check the official sweepstakes rules by clicking the link at the bottom of the survey page.

- You must be a legal resident of one of the 50 United States or the District of Columbia.

- Your age should be 18 years or above.

- You need a recent and valid purchase receipt from Taco Bell.

Wendys survey is designed to gather customer feedback. The purpose of wendys survey is to improve customer experience in regards to food quality and services provided by talktowendys.com. TalkToWendys encourage honest feedback so that they can focus on provided issues and concerns. Based on customer experience, employee improvement is noted and then Wendys make sure to focus on improving staff training.

Customers can take the wendys survey on talktowendys.com at any time. However, there are certain rules and regulations that you need to adhere in order to take and complete the Wendys survey successfully. Wendys survey doesn’t take long to complete, all you need to do is to answer a few questions based on your previous experience at TalkToWendys.

TalktoWendys Customer Survey

- Go to the official survey website at www.wendyswantstoknow.com

- Choose your language

- Now, enter the 8-digit restaurant number located at the top of your receipt

- Type the date as printed on the store receipt

- Enter your active email address

- Click next

- Read the questions carefully asked by the site.

- Answer each of them and if you wish, add any extra information in the space provided.

- After answering all questions, you will receive a coupon via your email address.

- Sign in to your email account and find the email from Wendy

- Print the coupon you received

- Congrats for getting a free coupon.

RULES

You must be 18 years of age, or older to participate in the survey.

You must have a purchase receipt from your recent visit to Wendy’s.

You have to take the survey in one language from English, French or Spanish.

You can only get one upon finishing the survey.

You must use the coupon before it expires.

INSTRUCTIONS

Visit any nearby Wendy’s and make a purchase.

Keep the purchase receipt with you.

Make sure you have a PC or a Smartphone with internet access.

Visit www.talktowendys.com from your PC or Smartphone.

Use the code that is printed on your receipt to enter into the survey.

Start the survey and answer all the questions to finish it.

You’ll receive a free coupon code after finishing the survey, save it.

Use the coupon code within the next 14 days to get your free BOGO Sandwich.

What are the questions about?

Just like any other survey, Wendy’s restoring survey questions are for faithful customers to answer. It comprises of questions about the restaurant and their services. They address some of the following issues:

- Restaurant services- They want to know how you were treated while on their premises? Where the workers friendly and did you get what you ordered? Did they get the order right? Also, is the premise clean as you want?

- Food quality and quantity- Did the quality of the food satisfy you, was it enough? Any issue about the cooking and serving of the food. They want to know your views on that. Did the food taste as you expected? Let them know so that they can change in the future.

- Payment services- How did you pay for your dish, did you have difficulties hen paying and which mode of payment would you like them to add? If you were purchasing for a takeaway, how was the process and was it as you wanted.

Whataburger has focused on its fresh, made-to-order burgers and friendly customer service since 1950 when Harmon Dobson opened the first Whataburger as a small roadside burger stands in Corpus Christi, Texas. Dobson gave his restaurant a name he hoped to hear customers say every time they took a bite of his made-to-order burgers: “What a burger!”

The reason behind restaurants conducting surveys is to know customers opinion on the food. To know whether the customer is satisfied or not. Customer satisfaction plays a crucial role in a restaurant’s success and progress. So Whataburger is also looking to ensure customer satisfaction. To know whether a customer is satisfied or not, you should ask. Hence, this survey from ChuckAlek Feedbacks.

Objectives of Whataburger Survey

There is a cost related to every action a company takes, so everything they do has a reason. So, a company has objectives for everything you do. So, let’s have a look at the objectives of Whataburger behind this survey:

- To get to know the customer’s point of view, how they judge the services of the restaurant they went to.

- To ensure that they are satisfying their needs and expectations. But to fulfill their expectations, they need to know what the expectations are in the first place. And to know the expectations, a survey is the best method.

- To help the restaurant improve various aspects of it by knowing what the customer thinks about it.

- This survey also helps the management to figure out how a store is performing.

- If something goes wrong, customers can help throw light at it and the problem can be dealt with at the management level itself.

How To Participate In The Whataburger Survey

Before participating in the survey, one must know the rules and regulations one needs to follow and fulfill. Read each and every point carefully. Here you go

Rules and Regulations

- The person participating in the survey should be a legal resident of The United States of America.

- The bill receipt should be of a recent visit and should be valid.

- The specific person participating in the review should be of an age 16 years and above.

- One must participate in the survey within a limited period of time from the visit. The receipt might be noted as invalid if you are too late.

- With one receipt one customer can participate only once. If you have more than one receipt then the same person can participate once more.

- The employees of Whataburger or their family members or agents are not eligible to participate in the survey.

- After the completion of the survey, you will receive a gift card. Make sure you redeem your gift card before it expires.

How To Take The Whataburger Survey

- Purchase something at a Whataburger and save your receipt

- Visit the Whataburger Survey page and take the online survey

- If your receipt doesn’t have a survey code, take the survey here instead

- Save your code to redeem your free gift on your next Whataburger visit

Author Abdaud Rasyid[1],[2], Mujaddid Idulhaq[1],[2], Pamudji Utomo[1],[2], Ambar Mudigdo[3], Handry Tri Handojo[4]

[1]Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Faculty of Medicine, Sebelas Maret University, Surakarta, Indonesia,

[2]Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Prof. DR. R. Soeharso Orthopaedic Hospital, Surakarta, Indonesia,

[3]Department of Anatomical Pathology, Sebelas Maret University, Surakarta, Indonesia,

[4]Department of Radiology, at Prof. DR. R. Soeharso Orthopaedic, Hospital, Surakarta, Indonesia.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Abdaud Rasyid,

Jalan Ahmad Yani, Pabelan, Kartasura, Sukoharjo, Jawa Tengah, 57162, Indonesia.

E-mail: abdaudry@gmail.com

Abstract

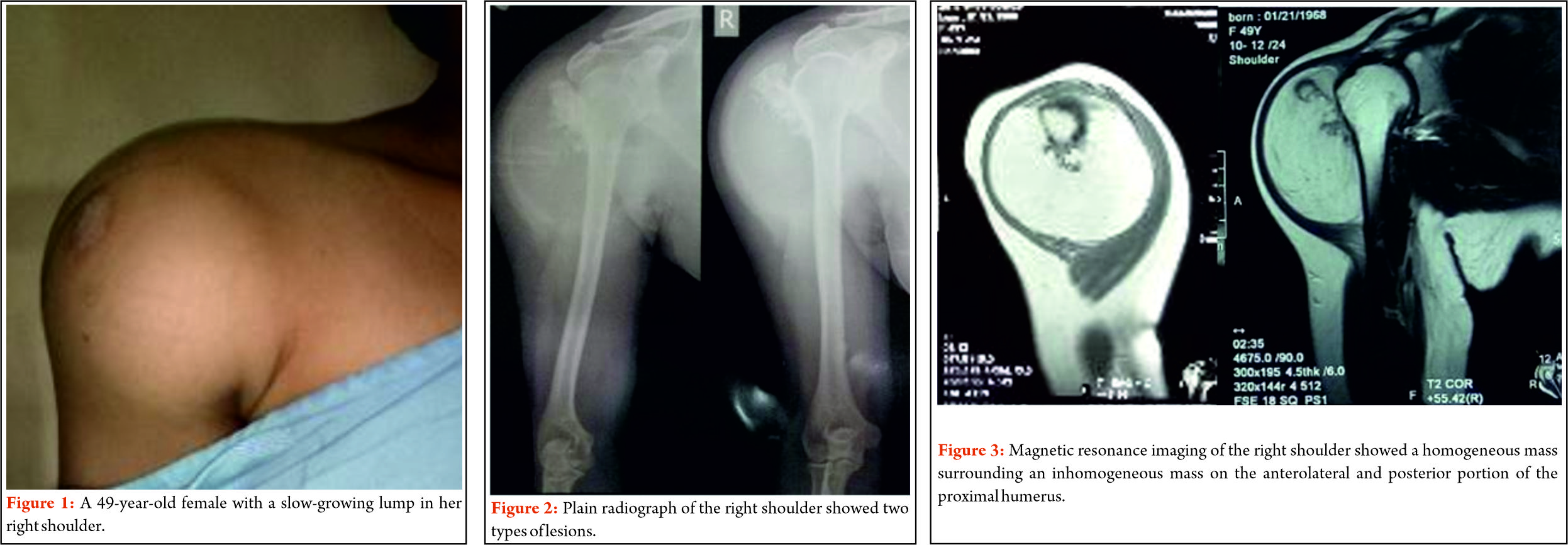

Introduction: Lipomas are the most frequent benign soft-tissue tumors. Soft -tissue lipomas are categorized by anatomic location as either superficial (subcutaneous) or deep (intermuscular). Deep lipomas can be located in any part of the body, including the superior extremities. Lipomas typically reach a diameter of several centimeters and are localized in a single anatomical region. Parosteal lipoma is a rare subtype of deep lipoma that has a broad attachment to the underlying periosteum that forms an exostoses-like bone prominence. There has been no reliable literature; about two pathological processes occur in one extremity at the same time.

Case Presentation: A 49-years -old female presented at our institution with a painless, slow -growing lump in her right shoulder region since for 2 years ago, with no other symptoms, and no history of trauma. A palpable non-tender mobile mass was present on the right shoulder region. Plain radiographs showed a well-delineated ovoid radiolucent lesion and a radiopaque lesion over the right proximal humerus. The fine -needle biopsy result suggested a liposarcoma. Wide-excision surgery was performed for both the masses. On contrary, the histological examination of the specimen confirmed a giant lipoma with pieces of adult bone tissues.

Conclusion: Deep-seated lipomas are most commonly discovered in men between the ages of thirties 30s and sixties60s. In our patient, the lipoma also accompanied with an exostoses-like cartilaginous mass over the proximal humerus as in parosteal lipoma. Plain radiographs study of parosteal lipoma is associated with a false osteochondroma appearance, which also found in this patient. Histological examination suggested a giant lipoma for this patient, but the possibility of two pathological processes is still in question.

Keywords: Giant lipoma, shoulder, exostosis, surgery.

References

1. Slavchev S, Georgiev PP, Penkov M. Giant lipoma extending between the heads of biceps brachii muscle and the deltoid muscle: Case report. J Curr Surg 2012;2:146-8.

2. Stevenson J, Parry M. Tumours. In: Apley and Solomon’s System of Orthopaedics and Trauma, 10th ed. Vol. 9. Ch. 9. Florida: CRC Press; 2018. p. 223-4.

3. Singh V, Kumar V, Singh AK. Case report: A rare presentation of giant palmar lipoma. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016;26:21-3.

4. Elbardouni A, Kharmaz M, Salah Berrada M, Mahfoud M, Elyaacoubi M. Well-circumscribed deep-seated lipomas of the upper extremity. A report of 13 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2011;97:152-8.

| How to Cite this article: Rasyid A, Idulhaq M, Utomo P, Mudigdo A, Handojo H T. A Giant Parosteal Lipoma with Exostosis of the Right Proximal Humerus. Journal of Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors May-August 2019;5(2): 4-7. |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com

]]>

Author: Yogesh Panchwagh [1], Ashish Gulia [2], Ashok Shyam [1,3].

[1] Orthopaedic Oncology Clinic, Pune, India.

[2] Orthopedic Oncology Services, Department of Surgical Oncology, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai.

[3] Indian Orthopaedic Research Group, Thane, India,

[4] Sancheti Institute for Orthopaedics &Rehabilitation, Pune, India

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Yogesh Panchwagh.

Orthopaedic Oncology Clinic, 101, Vasant plot 29, Bharat Kunj Society -2, Erandwana, Pune – 38, India.

Email: drpanchwagh@gmail.com

JBST- Special IMSOS 2019 Issue

JBST is entering the fifth year of publication . This would not have been possible without the help of the contribution by authors, guest editors, reviewers and the publication house team.

We take this opportunity to thank each and every one of them. Already indexed with Index Copernicus, google scholar and ETH Bibliothek , JBST is very close to pubmed indexation.

Our attempt over the last few issues has been to emphasise on publishing original work than invited or review articles so as to make the journal the chosen one for all those working in the field of bone and soft tissue tumors. We continue to bring to the readers the current concept in management of common bone and soft tissue tumors and tumor like conditions through sections like Students corner which is very useful for residents and consultants alike.

JBST is now affiliated with the IMSOS ( Indian musculo skeletal oncology society) and APMSTS ( Asia Pacific musculo skeletal oncology society) and will be showcasing their activities from time to time. Members of these associations can have the benefit of availing the opportunity of freely publishing in JBST. We are sure that this will add a new dimension and depth to the content of the journal.

We would like to thank the readers for their contribution and would like to hear from you about your experience and feedback so as to make JBST better.

Dr. Yogesh Panchwagh

Dr. Ashish Gulia

Dr. Ashok Shyam

| How to Cite this article: Panchwagh Y, Gulia A, Shyam AK. JBST – Special IMSOS 2019 Issue. Journal of Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors Jan-April 2019; 5(1):1. |

(Abstract Full Text HTML) (Download PDF)

]]>

Author: Michael Parry[1], Robert Grimer[1]

[1] The Royal Orthopaedic Hospital, Birmingham, UK.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Michael Parry.

Royal Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Bristol Road South ,Northfield, Birmingham

B31 2AP, United Kingdom

Email: michael.parry3@nhs.net

Abstract

Significant progress has been made in the management of paediatric osseous sarcoma. Where historically this diagnosis conferred a dismal prognosis, modern strategies of oncological management have resulted in significant improvements in disease free survival. These improvements have resulted in a broadening of the feasibility of limb salvage, which, in the paediatric population, presents its own unique challenges. Treatment must prioritize life over limb and not compromise local control for the advantage of cosmesis, limb length or function. Limb salvage, where possible, offers distinct advantages over conventional amputations and with the advent of modern techniques and technologies, should always be a consideration in the paediatric sarcoma population.

Keywords: Limb salvage, paediatric sarcoma.

Introduction

Primary malignant tumours arising from bone are relatively rare in the paediatric and adolescent population, accounting for only 6% of childhood malignancies. Of these, the majority (>90%) comprises osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma. Other bone sarcomas including chondrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant giant cell tumours, and adamantinoma can occur in the paediatric population although their incidence is relatively low. In these rare tumours, surgery is the first choice for local control.

Historically, an extremity sarcoma in a child conferred a dismal prognosis. However, advances in imaging modalities, greater understanding of the role of local control, and the use of multi-agent chemotherapy, has resulted in a significant improvement in overall survival. Such advances have resulted in an increase in 5-year survival from 10-20% to 60-70% with modern techniques. Thanks to these improvements in overall survival and a groundswell of interest and advances in technology, limb salvage is now regarded as the gold standard of treatment for those presenting with osseous extremity sarcoma. Advances in bone banking and an appreciation of the behavior of prosthetic replacement have improved surgical outcomes in limb salvage, though they have created their own complications. The aim of this review is to explore the advances in limb salvage surgery for osseous sarcoma in the paediatric population.

Patient Assessment and Diagnosis

Patients presenting with a suspected sarcoma should be managed in a specialist institution with the expertise and multi-disciplinary facilities necessary for the holistic care of the patient throughout their cancer journey. This is no more apparent than in the paediatric population where treatment decisions must be agreeable not only to the patient but also to their parent or carer.

In all patients, a detailed history and examination is mandatory. Whilst the majority of sarcomas are sporadic, rare familial conditions, including Retinoblastoma and Li Fraumeni syndrome, should be identified. The physical examination must include assessment not only of the lesion but also the distal neurovascular status of the limb.

Radiography must include a plain radiograph of the affected bone or limb segment as this will form the basis of the diagnosis. Further, detailed cross sectional imaging, most commonly with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will allow local staging. Systemic staging of the disease necessitates computerized tomography (CT) of the chest, as well as skeletal imaging, either in the form of a technicium Tc-99m scan, or whole body MRI. Systemic staging may include positron emission tomography (PET) in conjunction with a CT scan, though this is dependent on local and institutional guidelines.

Biopsy remains the cornerstone of confirmation of diagnosis for any suspected malignancy arising from bone. Improperly performed biopsies can result in a delay in treatment, hinder subsequent attempts at limb salvage, and result in an increase in local recurrence. MRI prior to biopsy helps identify the optimal position for biopsy and avoids distortion of the imaging by post-biopsy changes. The biopsy should be performed in such a way that the tract can be completely excised at the time of definitive resection and should be performed by a surgeon familiar with the techniques of limb salvage. The use of image guidance with ultrasound or CT is especially pertinent in the paediatric population where considerable contamination can occur with open biopsy techniques.

General Treatment Considerations

It is imperative that discussions regarding treatment are conducted in the setting of a multi-disciplinary team including specialists in paediatric oncology, radiology, histopathology and orthopaedic oncology surgery. Having established the diagnosis, in terms of histological type and grade, and staged the local and systemic burden of disease, discussion turns to local control. The timing of local control varies dependent on diagnosis and stage. Most strategies utilize systemic chemotherapy prior to definitive local control. This allows the treatment of metastatic or suspected micro-metastatic disease to be instigated immediately. This time lapse allows careful planning of the definitive surgical resection, allowing time for custom made implants or grafts. It also allows an assessment to be made of the tumour response to neo-adjuvant therapies, which often guides adjuvant therapy following tumour resection. In some cases, neo-adjuvant therapy results in a dramatic change in the tumour facilitating subsequent resection. The modality for local control must take into consideration patient, tumoural, socio-economic, cultural and technical biases.

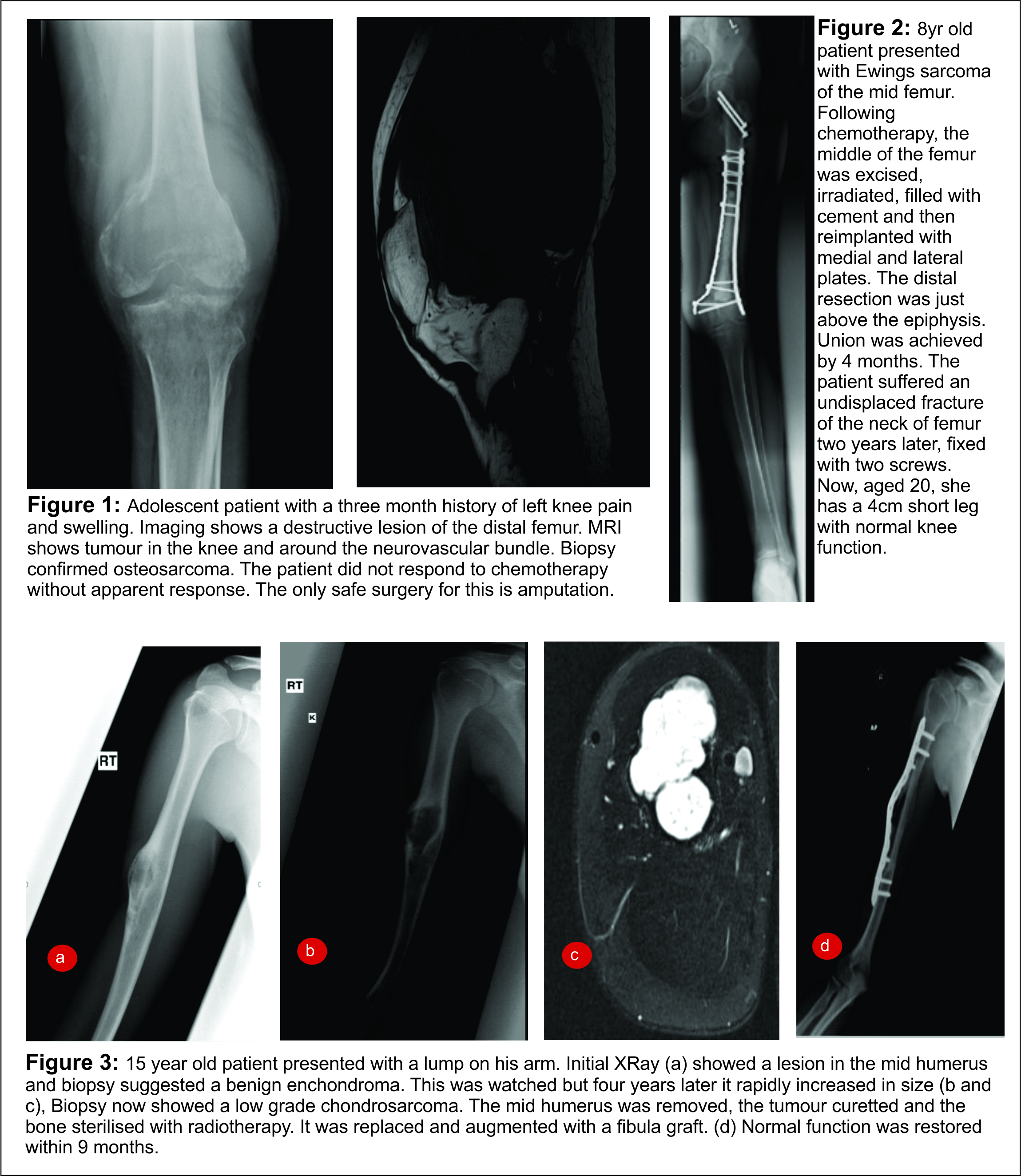

Amputation versus Limb Salvage

Whilst no absolute contraindications to limb salvage exist, the involvement of neurovascular structures which preclude attainment of a clear margin without significant impairment of limb function, and very young skeletal age, should point away from limb salvage as the definitive local control. Relative contraindications include factors resulting in a delay in reinstating systemic therapy, including infection and post operative wound complications, and factors most likely to result in an increase in local recurrence, including tumour bed contamination from inappropriate biopsy, expected positive surgical margins and pathological fracture (Fig. 1).

Patient wishes must be respected when considering amputation or limb salvage. The majority of studies comparing function in these two treatment groups have looked at tumours of the distal femur. No statistically significant difference has been demonstrated in the overall or disease specific outcomes between these two approaches, which is a manifestation of appropriate patient selection. According to the available outcome scores, function following amputation is comparable to that of limb salvage, with comparable psychological end points. Patients with limb salvage will often have a superior cosmetic result but often at the expense of endurance in certain physical activities. Patients undergoing limb salvage will undergo more surgical interventions than their amputation counterparts and patients and their families should be made aware of the lifetime of surveillance and repeated surgical interventions at the outset. However, financial considerations should not sway the intervention, especially as amputation patients will require a greater lifetime expense than their limb salvage counterparts.

Limb Salvage Surgery

When considering surgery for local control in osseous malignancies of the immature skeleton, consideration must be given to the tumour location and the sensitivity to oncological treatment modalities. For tumours sensitive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, (especially Ewings sarcoma), in challenging locations where surgical resection will result in unacceptable morbidity or an uncontaminated margin will be difficult to achieve, then non-surgical interventions may be more appropriate. Alternatively, for tumours not sensitive to radiotherapy, such as osteosarcoma, surgical resection may be the only option for local control, regardless of the morbidity. Surgery for the primary tumour and for metastatic deposits should be considered wherever possible. The aim in all surgery is to obtain as wide a margin of clear tissue as possible around the tumour. The better the response of the tumour to neoadjuvant treatment the safer limb salvage surgery becomes. Local control is indispensible for the cure of patients with Ewing’s sarcoma. Intralesional resection is associated with an increased risk of local recurrence and distant metastases.

Resection Without Reconstruction

For tumours arising in dispensable bones in the immature skeleton, including sections of the ulna, the scapula, the sacrum, the pelvis and fibula, local control can be achieved through excision without reconstruction. Excellent functional outcomes can be achieved without reconstruction, more so in the adaptable paediatric population.

Resection and Reconstruction

Biological Reconstruction

Autograft The large bony defect created following resection of an osseous malignancy often necessitates reconstruction for preservation of function and continued skeletal growth. The use of non-vascularised autologous structural bone graft dates back 100 years , whilst the use of a vascularized fibula graft was first described by Taylor in 1975. The blood supply of the vascularized graft is preserved by anastomosing its feeding vessel to a host artery. The graft subsequently undergoes revascularization from this vessel and from the surrounding vascular bed. Since its first description, this technique, as well as the use of non vascularized grafts, has been extensively described and applied. The technique lends itself best to reconstruction of intercalary long bone defects, or for proximal humeral osteoarticular reconstruction where the fibula provides not only structural support but also allows longitudinal growth of the limb segment from the proximal physeal plate. Special consideration should be given to resection of pelvic sarcomas where autograft reconstruction is being considered. An option for reconstruction in the adolescent age group, at or approaching skeletal maturity, is resection, extracorporeal sterilization and reimplantation. This has been reported as a viable method for reconstruction. Indeed, in their latest series reporting the use of this technique, Wafa et al reported a successful outcome in patients as young as 8 years old. This technique can also be applied to other body sites, particularly for intercalary reconstruction (Figs. 2 &3).

Allograft Improvements in tissue banking have allowed an expansion in the use of cadaveric osseous and osteoarticular allografts. Grafts are harvested and sterilized either by freezing or irradiation and can be offered on a custom made, size matched basis. There are mixed reports on the viability of articular cartilage following sterilization and the cadaveric bone itself is incorporated at best only moderately at osteosynthesis sites and beneath the periosteal sleeve, making the allograft at best a biomechanical scaffold. Depending on the site of reconstruction, up to 50% of patients undergoing allograft reconstruction can expect at least one complication, including infection, non-union or graft fracture. Some have reported infection rates following allograft reconstruction to be twice that seen following reconstruction with an endoprosthetic replacement. In spite of these potential problems, patients who avoid complications following allograft reconstruction function at a high level without the requirement for repeated revision procedures seen in endoprosthetic replacement.

In the case of adamantinoma and osteofibrous dysplasia like adamantinoma of the tibia, resection and reconstruction can be achieved either without reconstruction in the case of small, unicortical lesions, or with reconstruction using allograft, or autologous fibula graft. The fibula can be transferred and stabilized either in conjunction with a tibial allograft stabilized with plates or with the assistance of a ring external fixator.

In cases of diaphyseal resections, reconstruction can be achieved with intercalary allograft where the native joint above and below the lesion can be preserved. In many cases, particularly in Ewing’s and osteosarcoma, the tumour extends to the metaphysis, sparing the physis. Careful dissection can allow removal of the tumour without injury to the physis, preservation of the native cartilage and ligamentous attachments. Reconstruction of the diaphyseal defect with an intercalary allograft stabilized with an intermedullary nail through the centre of the physis allows continued growth at the physis. Incorporation of the allograft can be augmented by the addition of a vascularized fibula graft within the allograft. For tumours involving the distal femur or proximal tibia in young patients, an alternative option for reconstruction, preserving the foot, is an intercalary resection, and tibial turn-up (Van Nes) arthroplasty. The residual limb is rotated through 180o, the ankle joint now forming the novel knee joint. The resultant limb has the cosmetic appearance of an above knee amputation whilst allowing the capacity for longitudinal growth, if the proximal tibial physis has been preserved. Following rotationplasty, a prosthesis can be worn at the knee allowing ambulation. Gait analysis demonstrates improved kinematics when compared to a conventional above knee amputation. Careful consideration should be given not only to the technical demand of the procedure, but also the psychological impact on the patient and family of the disfiguring but highly functional procedure. The fact that the patients have no phantom pain is a distinct advantage over amputation at a similar level.

Non-Biological Reconstruction

Significant advances have been made in the design and manufacture of endoprostheses in the last 30 years. The advent of neo-adjuvant chemotherapeutic regimens has allowed an acceptable time lag between diagnosis and local control which allows for the manufacture of custom made endoprostheses based on the patients’ particular anatomy without delaying treatment. Primitive devices suffered from errors in manufacture resulting in implant fractures and early loosening with non-rotating knee prostheses. The current generation of endoprostheses offer an attractive life span for the majority, failure largely attributable to stress shielding in long stem endoprostheses and particle-induced osteolysis due to wear at the bearing interface. Failure is largely dependent on anatomical location, with proximal humeral and proximal femoral devices faring best, whilst distal femoral and proximal tibial prostheses perform less well. Patients with endoprostheses will undoubtedly require revision surgery within their lifetime, each time requiring greater osseous and soft tissue resection. The risk of infection remains high and increases with each revision procedure, leading, in the worst-case scenario, to possible amputation. This risk is increased when radiotherapy is employed, particularly for endoprosthetic reconstruction of the proximal tibia.

In younger patients, with more than 2 years of growth remaining, the issue of limb-length equalization is a real concern, particularly at the distal femur, where the physis here accounts for the majority of longitudinal growth. In such patients, “growing” prostheses present an attractive answer. Prostheses incorporating a growing distraction device can allow predictable lengthening and equalization of leg lengths. Minimally invasive growing prostheses (Fig. 4), where the device is lengthened by a distraction screw, accessed through a small incision, can be used in patients where surveillance of local recurrence is expected to require MRI. In those where local recurrence is unlikely, a non-invasive growing prosthesis (Fig. 5) can be employed. In such devices, the prosthesis incorporates a magnetic motor activated by an external rotating magnet applied in close proximity to the limb. This overcomes the need for repeated surgical procedures, and the inherent risk of infection this carries. However, patients with such devices cannot undergo further MRI scanning due to the irreparable damage this incurs on the magnetic motor. Whichever endoprosthetic device is chosen, consideration should be given to the method of fixation to native bone. The failures of early devices, attributable to particle-mediated osteolysis, have, to a certain extent, been obviated by the use of hydroxyapatite collars, essentially sealing the medullary canal and implant-bone interface from particulate wear generated at the bearing surface[53,54].

Conclusion

The paucity of algorithms to guide treatment strategies in paediatric patients with osseous sarcomas is a reflection of the multifactorial influences that predict outcomes following resection. An appropriate strategy can only be achieved following careful consideration of oncological, pathological, surgical and patient factors. Whichever strategy is adopted, the sequence of priorities should always be first life, then limb, then function, with leg length discrepancy and cosmetic appearance affording lesser consideration. When true equipoise exists between limb salvage and limb sacrifice, in terms of overall and disease-free survival, consideration must be given to limb function not only in the immediate periods following reconstruction, but also for the entirety of the life of the patient. In the case of the paediatric population, this may exceed the professional lifetime of the treating surgeon.

References

1. Arndt CAS, Crist WM. Common musculoskeletal tumors of childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(5):342–52.

2. Meyer JS, Nadel HR, Marina N, Womer RB, Brown KLB, Eary JF, et al. Imaging guidelines for children with Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group Bone Tumor Committee. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2008. pp. 163–70.

3. Mankin HJ, MANKIN CJ, Simon MA. The hazards of the biopsy, revisited. for the members of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. The American Orthopedic Association; 1996;78(5):656–63.

4. Brisse H, Ollivier L, Edeline V, Pacquement H, Michon J, Glorion C, et al. Imaging of malignant tumours of the long bones in children: monitoring response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and preoperative assessment. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34(8):595–605.

5. Harris IE, Leff AR, Gitelis S, Simon MA. Function after amputation, arthrodesis, or arthroplasty for tumors about the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Inc; 1990;72(10):1477–85.

6. Rougraff BT, Simon MA, Kneisl JS, Greenberg DB, Mankin HJ. Limb salvage compared with amputation for osteosarcoma of the distal end of the femur. A long-term oncological, functional, and quality-of-life study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Inc; 1994;76(5):649–56.

7. Simon MA, Aschliman MA, Thomas N, Mankin HJ. Limb-salvage treatment versus amputation for osteosarcoma of the distal end of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(9):1331–7.

8. Weddington WW, Segraves KB, Simon MA. Psychological outcome of extremity sarcoma survivors undergoing amputation or limb salvage. Journal of Clinical …. 1985.

9. Refaat Y, Gunnoe J, Hornicek FJ, Mankin HJ. Comparison of quality of life after amputation or limb salvage. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;397:298.

10. Grimer RJ, Carter SR, Pynsent PB. The cost-effectiveness of limb salvage for bone tumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(4):558–61.

11. Jurgens H, Exner U, Gadner H, Harms D, Michaelis J, Sauer R, et al. Multidisciplinary treatment of primary Ewing’s sarcoma of bone. A 6-year experience of a European Cooperative Trial. Cancer. 1988;61(1):23–32.

12. Craft A. Long-term results from the first UKCCSG Ewing’s tumour study (ET-1). European Journal of Cancer. 1997;33(7):1061–9.

13. Paulussen M, Ahrens S, Dunst J, Winkelmann W, Exner GU, Kotz R, et al. Localized Ewing Tumor of Bone: Final Results of the Cooperative Ewing’s Sarcoma Study CESS 86. 2001.

14. Burgert EO, Nesbit ME, Garnsey LA, Gehan EA, Herrmann J, Vietti TJ, et al. Multimodal therapy for the management of nonpelvic, localized Ewing’s sarcoma of bone: intergroup study IESS-II. Journal of Clinical …. 1990.

15. Nesbit ME, Gehan EA, Burgert EO, Vietti TJ, Cangir A, Tefft M, et al. Multimodal therapy for the management of primary, nonmetastatic Ewing’s sarcoma of bone: a long-term follow-up of the First Intergroup study. Journal of Clinical …. 1990.

16. Elomaa I, Blomqvist CP, Saeter G, Åkerman M. Five-year results in Ewing’s sarcoma. The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group experience with the SSG IX protocol. European Journal of …. 2000.

17. Schuck A, Ahrens S, Paulussen M, Kuhlen M, Könemann S, Rübe C, et al. Local therapy in localized Ewing tumors: results of 1058 patients treated in the CESS 81, CESS 86, and EICESS 92 trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55(1):168–77.

18. Krieg AH, Hefti F. Reconstruction with non-vascularised fibular grafts after resection of bone tumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(2):215–21.

19. Taylor GI, Miller GDH, Ham FJ. The free vascularized bone graft: a clinical extension of microvascular techniques. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1975;55(5):533.

20. DiCaprio MR, Friedlaender GE. Malignant bone tumors: limb sparing versus amputation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(1):25–37.

21. Zaretski A, Amir A, Meller I, Leshem D, Kollender Y, Barnea Y, et al. Free fibula long bone reconstruction in orthopedic oncology: a surgical algorithm for reconstructive options. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;113(7):1989–2000.

22. Belt PJ, Dickinson IC, Theile DRB. Vascularised free fibular flap in bone resection and reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58(4):425–30.

23. Beris AE, Lykissas MG, Korompilias AV, Vekris MD, Mitsionis GI, Malizos KN, et al. Vascularized fibula transfer for lower limb reconstruction. Microsurgery. 2011 Feb 25;31(3):205–11.

24. Petersen MM, Hovgaard D, Elberg JJ, Rechnitzer C, Daugaard S, Muhic A. Vascularized fibula grafts for reconstruction of bone defects after resection of bone sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2010;2010:524721.

25. Ad-El DD, Paizer A, Pidhortz C. Bipedicled Vascularized Fibula Flap for Proximal Humerus Defect in a Child. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2001;107(1):155–7.

26. Krieg AH, Mani M, Speth BM, Stalley PD. Extracorporeal irradiation for pelvic reconstruction in Ewing’s sarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91-B(3):395–400.

27. Khattak MJ, Umer M, Haroon-ur-Rasheed, Umar M. Autoclaved Tumor Bone for Reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;447:138–44.

28. Uyttendaele D, De Schryver A, Claessens H, Roels H, Berkvens P, Mondelaers W. Limb conservation in primary bone tumours by resection, extracorporeal irradiation and re-implantation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70(3):348–53.

29. Chen WM, Chen TH, Huang CK, Chiang CC, Lo WH. Treatment of malignant bone tumours by extracorporeally irradiated autograft-prosthetic composite arthroplasty. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2002;84(8):1156–61.

30. Sys G, Uyttendaele D, Poffyn B, Verdonk R, Verstraete L. Extracorporeally irradiated autografts in pelvic reconstruction after malignant tumour resection. International Orthopaedics (SICOT). 2002;26(3):174–8.

31. Wafa H, Grimer RJ, Jeys L, Abudu AT, Carter SR, Tillman RM. The use of extracorporeally irradiated autografts in pelvic reconstruction following tumour resection. Bone Joint J. 2014 Oct;96-B(10):1404–10.

32. Enneking WF, Campanacci DA. Retrieved human allografts : a clinicopathological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(7):971–86.

33. Mankin HJ, Springfield DS, Gebhardt MC, Tomford WW. Current status of allografting for bone tumors. Orthopedics. 1992;15(10):1147–54.

34. Fox EJ, Hau MA, Gebhardt MC, Hornicek FJ, Tomford WW, Mankin HJ. Long-term followup of proximal femoral allografts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(397):106–13.

35. Ortiz-Cruz E, Gebhardt MC, Jennings LC. The Results of Transplantation of Intercalary Allografts after Resection of Tumors. A Long-Term Follow-Up Study*. The Journal of Bone & …. 1997.

36. Muscolo DL, Ayerza MA, Aponte-Tinao LA, Ranalletta M. Partial epiphyseal preservation and intercalary allograft reconstruction in high-grade metaphyseal osteosarcoma of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(12):2686–93.

37. Grimer RJ. Surgical options for children with osteosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(2):85–92.

38. Van Ness CP. Transplantation of the tibia and fibula to replace the femur following resection. “Turn-up plasty of the leg”. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1964;46:1353–5.

39. Fuchs B, Kotajarvi BR, Kaufman KR, Sim FH. Functional outcome of patients with rotationplasty about the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;415:52–8.

40. Jeys LM, Kulkarni A, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, Tillman RM, Abudu A. Endoprosthetic reconstruction for the treatment of musculoskeletal tumors of the appendicular skeleton and pelvis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Inc; 2008;90(6):1265–71.

41. Malawer MM, Chou LB. Prosthetic survival and clinical results with use of large-segment replacements in the treatment of high-grade bone sarcomas. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(8):1154–65.

42. Unwin PS, Cannon SR, Grimer RJ, Kemp HB, Sneath RS, Walker PS. Aseptic loosening in cemented custom-made prosthetic replacements for bone tumours of the lower limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(1):5–13.

43. Ward WG, Yang R-S, Eckardt JJ. Endoprosthetic bone reconstruction following malignant tumor resection in skeletally immature patients. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27(3):493–502.

44. Kawai A, Muschler GF, Lane JM, Otis JC, Healey JH. Prosthetic knee replacement after resection of a malignant tumor of the distal part of the femur. Medium to long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998 May;80(5):636–47.

45. Jeys LM. Periprosthetic Infection in Patients Treated for an Orthopaedic Oncological Condition. J Bone Joint Surg Am. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Inc; 2005 Apr 1;87(4):842–9.

46. Lewis MM. The use of an expandable and adjustable prosthesis in the treatment of childhood malignant bone tumors of the extremity. Cancer. 1986;57(3):499–502.

47. Hosalkar HS, Dormans JP. Limb sparing surgery for pediatric musculoskeletal tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004 Apr;42(4):295–310.

48. Eckardt JJ, Kabo JM, Kelley CM, Ward WG, Asavamongkolkul A, Wirganowicz PZ, et al. Expandable endoprosthesis reconstruction in skeletally immature patients with tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(373):51–61.

49. Finn HA, Simon MA. Limb-salvage surgery in the treatment of osteosarcoma in skeletally immature individuals. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(262):108–18.

50. Gupta A, Meswania J, Pollock R, Cannon SR, Briggs TWR, Taylor S, et al. Non-invasive distal femoral expandable endoprosthesis for limb-salvage surgery in paediatric tumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(5):649–54.

51. Beebe K, Song KJ, Ross E, Tuy B, Patterson F, Benevenia J. Functional outcomes after limb-salvage surgery and endoprosthetic reconstruction with an expandable prosthesis: a report of 4 cases. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(6):1039–47.

52. Kenan S. Limb-sparing of the lower extremity by using the expandable prosthesis in children with malignant bone tumors. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics. 1999;9:101–7.

53. Myers GJC, Abudu AT, Carter SR, Tillman RM, Grimer RJ. Endoprosthetic replacement of the distal femur for bone tumours: long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(4):521–6.

54. Myers GJC, Abudu AT, Carter SR, Tillman RM, Grimer RJ. The long-term results of endoprosthetic replacement of the proximal tibia for bone tumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007 Dec;89(12):1632–7.

| How to Cite this article: Parry M, Grimer R. Limb Salvage in Paediatric Bone Tumours. Journal of Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors Sep-Dec 2015;1(2): 10-16. |

|

|

(Abstract) (Full Text HTML) (Download PDF)

]]>